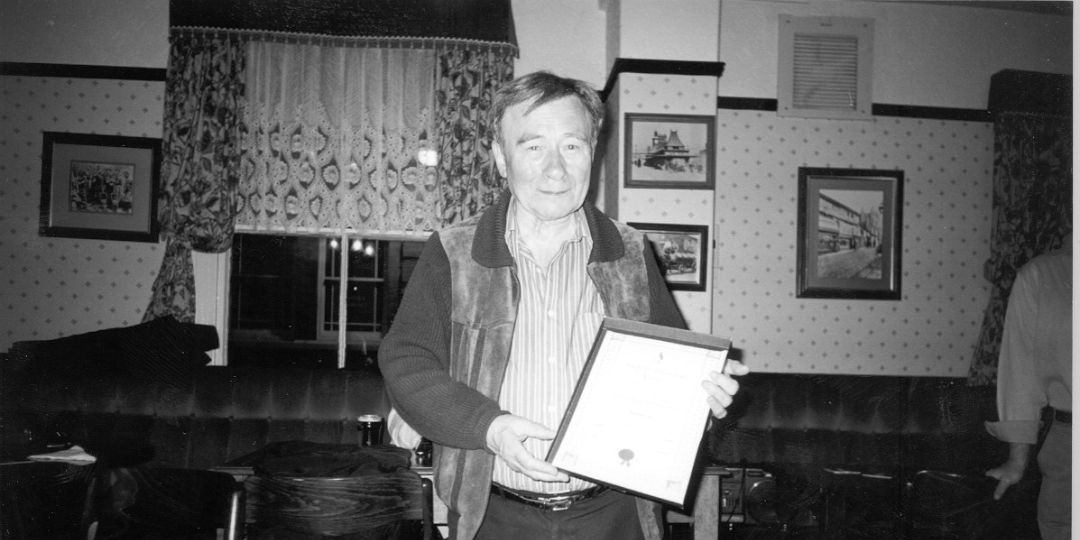

Bill McIlroy – The Ballynahinch Atheist

A recounting of the life and work of Bill McIlroy

Published: 29 August 2024

A recounting of the life and work of Bill McIlroy

Published: 29 August 2024

In March 1972, the Belfast Telegraph profiled William ‘Bill’ McIlroy, the 44-year-old secretary of the National Secular Society, a venerable secularist campaign group based in London.

Readers of the Telegraph may have been surprised to learn that this frankly spoken heretic, characterised as the ‘man who will not pray for us’, was originally a native of the village of Drumaness, near Ballynahinch, Co Down.

McIlroy’s life was by any measure, remarkable, not least that he overcame rural poverty in early life in Ireland to become a public figure in England. A largely self-taught intellectual and political campaigner of a kind perhaps more common in the 19th century, McIlroy was a journalist who manned the barricades of the culture wars of the 1970s.

As well as being a religious and political dissident whose views placed him completely at odds with his background, McIlroy was a queer migrant who had, like many others, left his homeland in search of a more tolerant climate elsewhere.

William McIlroy was born in Ballynahinch in 1927, the eldest son of James McIlroy and Margaret Cranstoun. His father had been a soldier in the British Army, and subsequently worked, when able to find employment, as a manual labourer in the linen industry.

Theirs was a large family - Bill had six siblings - and living conditions were tough in a rural house several miles from the town, and with no running water. There was little in this background, though, which suggested radical nonconformity.

Although the McIlroy’s family were members of the Church of Ireland, he was ‘saved’ by an evangelical tent mission in the early 1940s. However, disillusionment followed, and he became an outspoken critic of Christianity. This required to him to leave home, likely for his own safety, and he remained unwilling to return throughout his life. He found refuge with relatives in Coventry.

Working in various factories, he was recruited by the Communist Party of Great Britain, who he credited with providing him with some measure of education. In 1955, he married Margaret Hooker, a teacher, who he had met on a holiday for workers organised by the Party, and soon became the father of two daughters. The marriage was imperilled by Bill’s homosexuality, but an arrangement was made between the couple for it to be discreetly open, provided he remained as a parent.

Contrary to a stereotype of queer migrants as solitary figures exiled from family, McIlroy was not only the much loved father of daughters, but he was also a surrogate parent to younger siblings, whom he brought to England along with his widowed mother.

Following his apprenticeship in radical politics, most which remains shrouded in mystery due to the absence of an autobiography, Bill was appointed Secretary of the National Secular Society (NSS) in 1963. This organisation, a product of the 19th century, had once been vigorous, but was now antique and strapped for cash. McIlroy was its only full-time employee.

The moral conflicts of Sixties Britain, with traditional religion suddenly up for question and in conflict with an emerging social liberalism, offered the NSS an opportunity to revivify, which was grasped with determination by McIlroy and its then president, David Tribe. When he was profiled by the Belfast Telegraph, McIlroy was reported to be, ‘an active opponent of Christianity in all its forms’ who had ‘championed an assortment of causes including secular schools, euthanasia and an end of Sunday observance.’

He served several stints as editor of the Freethinker, then the NSS’s newspaper, and in the early 1970s his editorials kept up a running commentary on the battles between the ‘permissive society’ and its enemies. In 1971, Bill and Margaret McIlroy sensationally exposed the ‘sadistic’ use of corporal punishment in a Catholic school in London.

His most sustained scorn was, however, reserved for the self-appointed enemies of the ‘permissive society’, Mary Whitehouse and Frank Pakenham, Lord Longford. In 1973, McIlroy became secretary of the Committee Against Blasphemy Law, which had been founded to protest against Whitehouse’s revival of the blasphemy law, which had resulted in the trial and conviction of the editor of Gay News.

Bill’s editorials in the 1970s demonstrate how his commitment to humanist and secularist causes was combined with a broader anti-imperialism. And having emerged from a culture which lauded militarism, McIlroy held strong sympathies with pacifism. In 1994, he was, amongst other activists, instrumental in securing the construction of the Conscientious Objector’s Monument in Bloomsbury, in Central London.

Bill McIlroy’s need for funds to support his family required him to be a versatile figure. His work for the National Secular Society encompassed journalism, administration, publicity and work as a humanist celebrant conducting secular funerals. He was intermittently a civil servant, and, after moving to Brighton, worked in a sexual health clinic.

An intellectual by ability and temperament, McIlroy regretted his lack of formal education, and strove to ensure his daughters were not similarly handicapped.

Small of statue and slight in appearance, his voice, on surviving recordings, was one of a cultivated English accent soon giving way to an Ulster drawl. Bill’s attitude to his sexuality remained complex throughout his life. He was a longstanding and vocal supporter of gay rights in print and was characteristically scathing about their opponents, describing them as ‘prudes, conformists and political opportunists.’ At the same time, his own sexuality was shrouded in discretion, and sadly, he is not thought to have found contentment with a long term same-sex partner.

His friend and political co-conspirator, Barry Duke, characterised McIlroy as having been easily embarrassed by open discussions of homosexuality and remaining ‘half in-half-out of the closet.’

Margaret predeceased Bill by several years. He spent his retirement in Brighton, frequently writing to the local press on matters of secularist interest, and, interestingly, continuing to criticise imperialism at the time of the Iraq War.

He was, assisted by Barry Duke, the author of a pamphlet on the radical history of Brighton in the 19th century. In one of his final public interventions, he celebrated that Brighton had been declared the least religious city in England.

He died from cancer in 2023, his daughters having ensured that he had access to his beloved books to the last.

Belfast Telegraph, Brighton Argus, Freethinker, Charlie Lynch interview with Barry Duke, 2021, Charlie Lynch correspondence with Helen McIlroy, 2022, and Robert Stovold interview with Bill McIlroy, 2008.